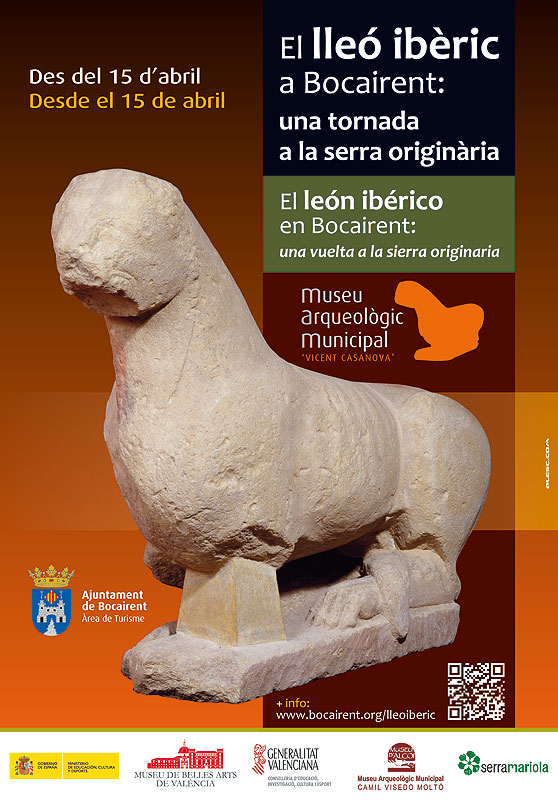

“The Iberian Lion of Bocairent: the sierra of origin revisited” constitutes a historical milestone marking the return, after an absence of 121 years, of the most representative sculpture in Bocairent’s history. The temporary loan of the figure by Valencia’s Fine Art Museum means that the full splendour of the sculpture can be admired at the foot of the Sierra Mariola where it was discovered by chance in the 19th century at a location on the Galbis hillock.

The occasion has also served to renew the installations of the “Vicent Casanova” municipal archaeological museum in order to hold the exhibition, which includes two pieces found on the same site from Alcoi’s “Camil Visedo Moltó” Museum. Moreover, the exhibition will be accompanied by a varied programme of activities further highlighting the return to Bocairent of one of its most important ancient artefacts.

Location:

Municipal Archaeological Museum ‘Vicent Casanova’ (Lion of Bocairent Square)

CREDITS

Coordination: Joan Castelló Cantó

Direction of Municipal Archaeological Museum ‘Vicent Casanova’: Isabel Collado Beneyto

Guide of Municipal Archaeological Museum ‘Vicent Casanova’: Ana M. Campello Antón

Design and web: Alesc Comunicació

Photographs:

Museum of Fine Arts of Valencia

Museum ‘Camil Visedo Moltó’ (Alcoi)

Town Council of Bocairent

Alesc Comunicació

Audiovisual: Documentart

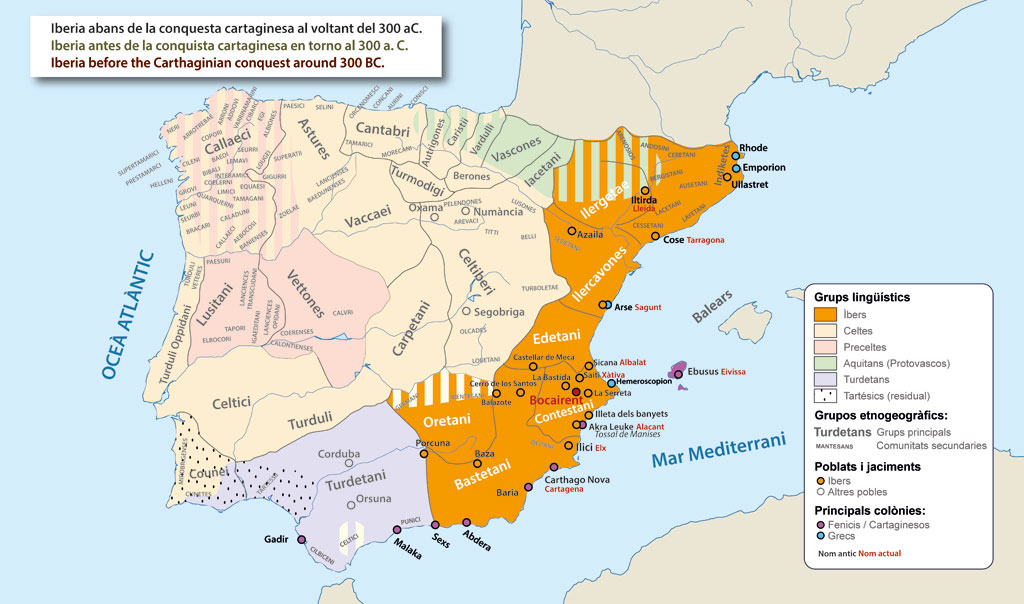

The Iberian domains extended along the eastern margins of the Iberian Peninsula up to the Rhône (with its estuary close to the French city of Avignon), and encompassed a civilisation characterised by two main periods. The first formative period began around the 6th century BC and was marked by Oriental and Hellenistic influences, whilst the second constituted a period of definitive consolidation that continued until the 5th century BC.

From a political perspective the Iberians were never a unified nation but instead were organised into city-states where the warrior aristocracy played a fundamental role. It was this military nobility, along with its tribal and economic peers, that formed the upper echelons of Iberian society.

The warriors made up an extensive social group and practised the so-called Iberian “devotio”, an institution based on the adhesion to a chieftain, who they protected and followed to the death even to the extent of carrying out collective suicides. They also subscribed to a type of clientelism that entailed submission and service to a warlord in exchange for protection. Furthermore, they followed the dictates of “hospitum”, a practice by which an outsider was incorporated as a member of the community.

The Iberian economic system was based on the exploitation of irrigated agricultural lands using draft animals, and to a lesser extent included livestock breeding. Mining also had a great deal of importance for this civilisation, as did the fabrication of esparto grass products, along with linen and woollen textiles.

The influence of the Greeks and the Phoenicians, along with the legacy of peninsular peoples from the Neolithic period, helped to forge the Iberian culture. In the religious sphere, the Iberians adhered to magical animistic beliefs related to the natural world. Furthermore, the practice of cremation was widely used in funeral rites.

The arrival of the Barcinos from Carthage in the 3rd century BC and the subsequent events that occurred in the Iberian Peninsula from this time onwards led to a gradual socio-economic and cultural transformation in favour of the Romans.

Joan Castelló Cantó

The northern slopes of the Sierra Mariola hold many archaeological remains that tell of human occupation in this area at different times in history. Those that are specifically related to the Iberians can be evidenced at the following sites: the Mariola peak (Alfafara-Bocairent), the Galbis hillock (Bocairent), the Serrelles peak (Alfafara), and the Sant Antoni peak (Bocairent).

From around the 9th to 8th centuries BC a group of peasants and farmers chose the Mariola peak to establish their homesteads, work the land, and exploit the natural resources provided by the sierra. Over time the settlement expanded and by the Iberian period (6th to 3rd centuries BC) it was already consolidated as an important fortified hilltop villages that articulated the territory of this region, and was used by the Iberians to ensure the protection and visual dominion of the surrounding area.

Apart from the large settlement at the Mariola peak, there was also an important site for Iberian religious practices located in the heart of the sierra: at the Galbis hillock, where the Iberian Lion was unearthed. Moreover, various Iberian pots and ceramic shards related to the sculpture were also discovered in the vicinity.

Another archaeological site of singular importance can be found at the Serrelles peak, at the foot of the Mariola peak, where a watchtower was erected on top of a small hillock. During a survey of the area a few years ago a room appeared containing ceramic vessels and more significantly, almost forty lead projectiles.

From the 1st century BC onwards these hilltop forts were abandoned giving way to a rural landscape dotted with settlements dispersed over the valleys. At the Sant Antoni peak a prominent settlement showing the remains of constructions can be found. The pottery unearthed at the site indicates that it was inhabited between the 1st and 4th centuries AD and was once a settlement of some importance.

GRAU, I. i SEGURA, J. M. (2015) «The Iberians in Mariola», in the programme of Fiestas of Sant Blai. Text adapted from: Bocairent, Association of Mores and Christians, Fiestas of Sant Blai.

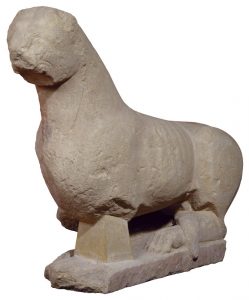

The Lion of Bocairent was discovered in the heart of the Sierra Mariola, between the Malladeta and Coveta fonts, at the source of the Vinalopó river. The exact location of the discovery corresponds to the Galbis hillock, one of the many Iberian archaeological sites in the area.

The sculpture was found by chance during the second half of the 19th century on the property of Vicent Calabuig i Carra, who later recounted the discovery to the archaeologist Enrique Pla Ballester:

“In the middle of the last century he went to dig a water deposit at the foot of the hill (the Galbis hillock) where the Malladeta font wells up from the sierra, close to the Brulls fountain, where the Vinalopó river has its source. It was found broken into two large parts and another smaller one, but he couldn’t locate the missing pieces for the front feet. It seems probable that the breakage was not fortuitous but rather intentional, because the local stone is extremely hard, and is colloquially known as Cordillera or Solana stone.“

Since then the name of Vicent Calabuig i Carra has been associated with the history of the Iberian lion. Born in 1852, this Bocairentine studied philosophy and law at the University of Valencia before teaching as a Professor of Law in Oviedo and Valencia, where he finally established himself. Calabuig i Carra was renowned as a professor, politician, writer and philosopher, but the town of Bocairent remembers him above all as the person who, in 1895, donated the sculpture of the Iberian lion to the San Carlos Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Valencia, currently the San Pio V Museum of Fine Arts.

Joan Castelló Cantó

The Iberian Lion of Bocairent was sculpted in yellow-grey limestone in the 4th century BC. It is a freestanding zoomorphic sculpture (made to be seen from all angles), which probably formed part of a funerary monument of the column-stela type. Within the Iberian representation of animals, the figure of the lion has a dual function; on the one hand to guard and protect the deceased and on the other hand to facilitate the deceased’s transition into the afterlife.

The Iberian Lion of Bocairent was sculpted in yellow-grey limestone in the 4th century BC. It is a freestanding zoomorphic sculpture (made to be seen from all angles), which probably formed part of a funerary monument of the column-stela type. Within the Iberian representation of animals, the figure of the lion has a dual function; on the one hand to guard and protect the deceased and on the other hand to facilitate the deceased’s transition into the afterlife.

This type of funerary monument, which was a symbol and expression of the Iberian aristocracy, is mainly found in the south east of the peninsula, upper Andalusia, and the provinces of Murcia, Albacete, Alicante, and the south of Valencia. The chronology stretches from the beginning of the 5th century BC to the middle of the 4th century BC.

The lion sculpture was already in a fairly dilapidated state of repair when it was donated to the San Carlos Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1895. It was originally supported on a cement and brick pedestal having been found in three parts with the front feet missing. During the initial intervention these fragments were joined together using iron pins along with lime and cement mortar.

Years later it underwent a final intervention. The restoration process, undertaken by the Valencia Fine Arts Museum Restoration Centre, entailed the elimination of the cement and brick pedestal whilst the metallic iron elements and remains of mortar from previous interventions were removed as well. Together with a process to clean and desalinate the sculpture, it also underwent a chemical treatment in order to detain the advance of live organisms and eliminate them.

The consolidation of the statue was performed by impregnating it with a resin, and anchoring the three parts using titanium bolts and bicomponent resin, which provides highly resistant bonding and structural seals. The internal parts of the fractures were sealed, first with hydraulic mortar and later with slaked lime mortar, marble powder and siliceous sand. At the same time limestone was used to hold the sculpture in place by the front feet.

Isabel Collado Beneyto

Tourist-Info Bocairent

Plaça de l'Ajuntament, 2

46880 Bocairent (Valencia)

Tel.: 96 290 50 62

bocairent@touristinfo.net

---

privacy • web map

cookies • accessibility